I attended an online Music Biz Association webinar last week presented by Mark Mulligan. Mulligan is the author of the Music Industry Blog, Managing Director of of MIDiA Research and “a media and technology analyst of more than 15 years’ standing and one of the leading voices in music industry analysis.”

I really like Mulligan’s blog posts because he is a music industry wonk, something I can only aspire to. His work is original and thorough. He often presents his research findings at music industry conferences.

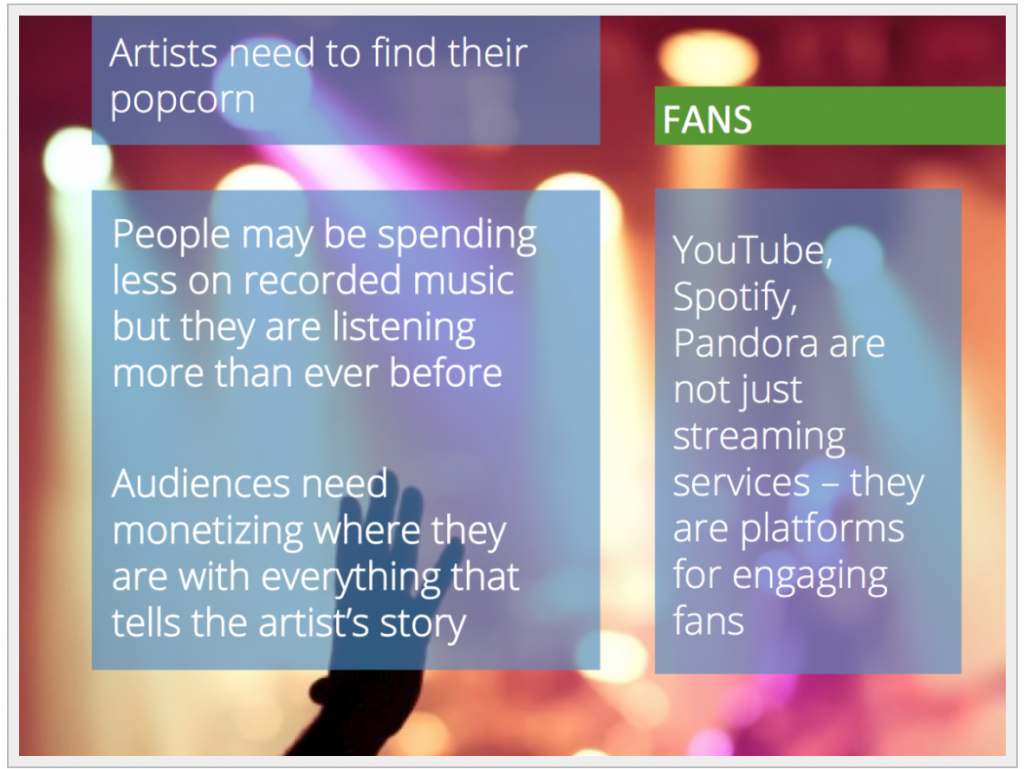

One of the ideas Mulligan presented in this webinar is that music itself is no longer a revenue-generating product for musicians. This has powerful implications for the average musician’s marketing strategy and tactics.

Because music is so much in abundance now (due to the digital democratization of both music production and distribution) it has effectively been commoditized down to zero price, so that makes it hard to make a living as a musician.

This is not a new idea, of course. The effect is even more pronounced for emerging artists or artists with niche appeal.

So what is a starving musician to do to keep themselves going?

[Tweet “Musicians, find your popcorn”]

Mulligan proposes that artists should follow the marketing model developed in the early days of the cinema (theater) business.

Here’s the basic idea (from a 2014 post on Digital Ascendency on Mulligan’s blog):

What do I mean by this? Well when the cinema industry started out it was a loss making business. To try to fix this cinemas started by experimenting with the product, putting on double bills but that wasn’t enough. Then came innovation in the format by adding sound. Then the experience itself by co-opting the new technology of air conditioning from the meat packing industry. Still no profit. Finally cinemas found the solution: popcorn. With a 97% operating margin, popcorn along with soda and sweets quickly became how cinemas become profitable entities. Artists need to find their popcorn. To find out what other value they can deliver their fans to subsidize releasing music.

The other example Mulligan gives is that of American tycoons like Leland Stanford and Levi Strauss who made their fortunes not from gold, but from selling shovels, blue jeans and other supplies to gold miners during the gold rush.

This idea that music is effectively the “loss leader” (not the real money-maker, but something that draws customers in to spend on other things) has been promoted for a while in music marketing circles.

This idea that music is effectively the “loss leader” (not the real money-maker, but something that draws customers in to spend on other things) has been promoted for a while in music marketing circles.

The question I always ask is, “OK, so what should artists be selling then in order to make a living?” or, in other words “What is the shovel today?”

Mulligan stresses that artists can still make money by offering fans “experiences in the context of the music.” Experiences, as we all know, are ephemeral, or in the moment, so they are, by definition, more scarce commodities. This makes them less vulnerable to the commoditization effect than recorded music.

[Tweet “What can artists sell to fans today besides music?”]

Some examples Mulligan mentioned that savvy musicians can still make money on are:

- live shows

- online streaming concerts like ConcertWindow, StageIt or YouNow

- backstage VIP passes and private meet-and-greets

- behind-the-scenes documentation of the creative or recording process

- limited edition, high margin merchandise

- personalized items such as hand-written lyrics

- direct-to-fan funding (crowdfunding) vehicles like Kickstarter, PledgeMusic, and Patreon, which give fans a way to support artists in a sustained and direct way.

[Tweet “Most crowdfunding artists miss the boat on what fans really want”]

These are all great ideas, in theory, but I find that artists don’t always know what their fans are willing to pay for. Finding the ‘popcorn’ isn’t as easy as it sounds.

Let’s talk crowdfunding premiums. I love crowdfunding, as a concept.

Here’s my concern: I have personally participated in dozens of crowdfunding campaigns. I think most artists miss the boat on what fans really want, however.

I have literally thrown away, shelved, boxed, and given away more crowdfunding premiums than I can count. I no longer have the autographed pictures and hand-written lyrics. I have many band T-shirts that I wear as pajamas. I also don’t often watch the home made living room videos of unreleased new songs. (Don’t tell those musicians, please).

Also, Musician =/ YouTube star. If we were all good at being YouTube stars, we’d do that for a living and screw the music business. Even Jack Conte ended up starting a software company instead of being a musician YouTube star.

I pay for these things because I want to support these artists, and I don’t want to offend them by not taking their premiums.

The other problem most musicians I know have is that designing and paying for merchandise that fans are willing to purchase is a tricky business.

I just sat with an artist client yesterday whose band used to offer some really cool merchandise at their shows, but they no longer do it because the wife of one of the former band members used to handle their merchandise design and ordering, and he’s no longer with the band. No one else in the band wants to take on doing the band merchandise. Also, the band doesn’t want to be saddled with a box of 200 T-shirts or 5000 bumper stickers. It’s a significant capital outlay to purchase physical merchandise.

[Tweet “Band merchandise is an expensive investment”]

On the other hand, a performance group that really does merch right is Cirque du Soleil. If you have ever been to one of their shows, you know exactly what I mean. It’s all branded, tied-in graphically, high quality, and high markup. The audience lines to buy it are out the door at intermission. It’s a memento of the show, of the “experience,” and it is expertly executed.

Cirque du Soleil has figured out how to sell ‘popcorn’ at their shows. And, by the way, they do sell actual popcorn at their shows, too. The keys are high margin and a captive, engaged audience who is thrilled to open their pocketbooks in the moment for items with good design, a clear event-tie in, and a big markup.

[Tweet “The keys are high margin and a captive, engaged audience”]

Unfortunately, merchandise design is just not the core competency of most bands. I do know bands who have done it right, and their merchandise really made their CD release shows or Kickstarter campaigns appealing (like my friends, musicians Aury Moore and Mary Bue McLean), so it can be done. Here’s Aury on what worked for her Kickstarter campaign:

The pledge items were fun! The ones that people loved the most were the really personal ones. We had a package for $222 [Aury is obsessed with this number, for reasons too long to go into here]. For your pledge of $222 you received a night of me cooking you dinner. We of course made a point to let you know that I can’t cook… We had 13 people pledge for me to cook them dinner anyways! A few other cool items were Eddie’s Hats. During our shows our drummer has this little shtick of him changing hats during the shows. The fans are constantely trying to catch him changing his hat… it is fun… well… Eddie gave away 12 of his hats. We also let someone shave his head and I gave away 2 hard board posters from my first CD release party. there were only a total of 3 made. 2 with autographs from all the people who played that show with me including Alan White of Yes and Michael Wilton of Queensryche. I have one of these for myself but I gave away the other 2 in my Kickstarter campaign. One with autographs and one without. People liked the one of a kind items. I also added more pledge packages by request from people who wanted to pledge. People asked me to add shot glasses and tshirts that would be autographed that were not the ones made for the campaign. I also had people negotiate with me… they offered to pledge if I would come out and perform a song with their band. I did this on two occasions.

[Tweet “Which fans are actually willing to pay for what?”]

I like the music fan segmented monetization strategy “Whale, Dolphin, Minnow” described on Billboard by Hany Nada, which segments customers by their financial purchasing power:

Like players in a casino, each music fan has a different value based on their inclination to spend. In the casino system, fans are divided into three segments: whales, dolphins, and minnows (WDM). Whales often make up the majority of the profits in the casino industry. These are the people willing to pay substantially more for an elite experience. Since whales are substantially more profitable than minnows (the casual players who just want to hit the slots and enjoy a buffet meal), the casino industry has always catered to them. Whales are treated to amazing services, including flights, suites, rebates on losses, private chefs, and shopping sprees – all in an aim to keep them spending freely at the card tables.

[Tweet “Segment offers to Super Fans, Main Fans and Passive Fans”]

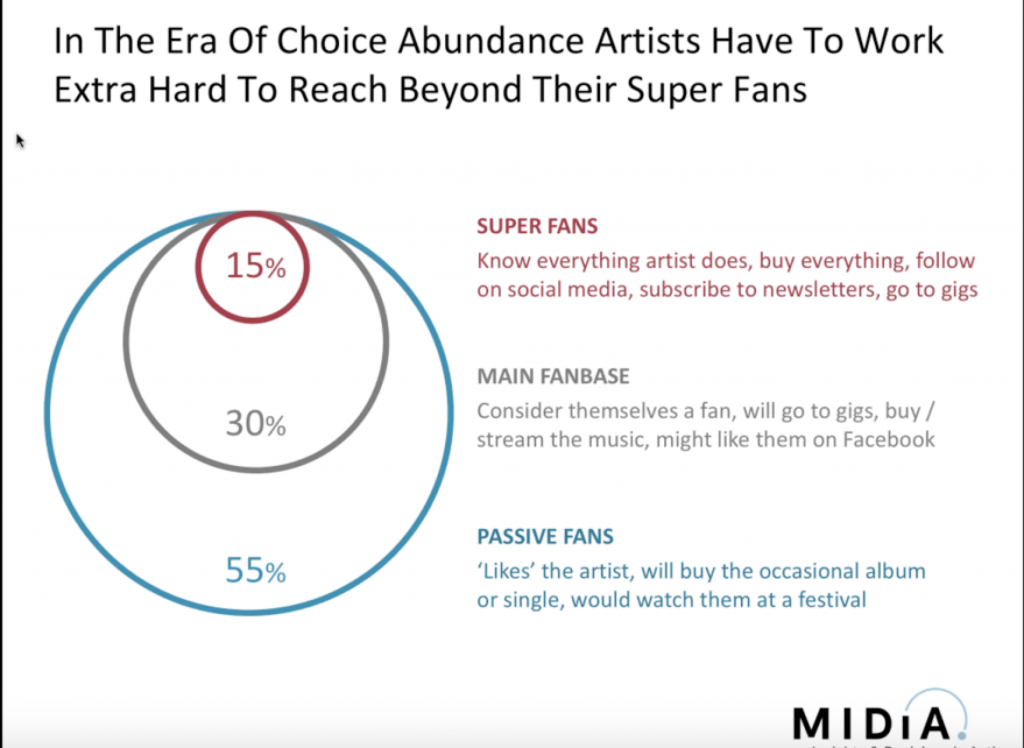

Mulligan’ also suggests segmenting the music fan into three main camps, but differentiating them instead by their level of interest in or loyalty to the artist:

My initial crowdfunding experience was with Amanda Palmer’s now-famous Kickstarter crowdfunding campaign. I think part of Palmer’s crowdfunding success (in addition of course to the fact that she already had a huge and very engaged social media following) was her astute choice of premiums, which catered to a wide variety of fans. She offered everything from house concerts for thousands of dollars to digital downloads for a lot less.

But even Amanda Palmer had trouble actually making a profit from her Kickstarter campaign and considered it a “loss leader leading to Patreon.” I was a Whale contributor, and I can personally attest that I receive a LOT of stuff from Amanda Palmer. One item ( avery high end coffee table photo book) weighed 30 lbs or more and I bet it cost a lot just to ship. I gave it away.

So, clearly, segmenting customers is important, but offerings at each level still need to adhere to the high margin principle.

[Tweet “Embrace fremium, engage, offer premium experiences, allow remixes, and crowdfund”]

Another way to look at the problem of “finding your popcorn” is to look to other digital media industries which have been successful in addressing the same issue the music industry faces. Creators and marketers in the PC video games industry (as well as other industries like movies, TV, and books) have many of the same issues as those of us in the music industry:

- the frictionless nature of digital creation, adoption, and consumption,

- proliferation of consumer choices and commoditization

- getting lost in the noise, or “discovery” and

- modification (remixing) and its attendant copyright/ownership/attribution issues (which are really all about making money).

[Tweet “Apply lessons from the PC video game industry to music”]

Chris Dixon offers five succinct keys to success for digital media creators in a recent post on Medium entitled “Lessons From The PC Video Game Industry” which I believe DIY musicians would be wise to heed.

Translating Dixon’s keys into actionable music marketing tactics for indie musicians:

- Embrace Fremium: Get your music up on all the streaming platforms like Pandora, Apple Music and Spotify (etc.), and don’t “hoard” it in the vain hope that this will discourage “piracy.” You cannot create scarcity, or value, with your music itself, because there are so many other choices. You’d be surprised how many musicians I know who are still very against posting their music on streaming platforms or offering free digital downloads or even streaming from their own website.

- Engage: Use social media like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and content marketing like videos, podcasts and blogging to engage with fans. Post and reply.

- Offer Premium Experiences: Do live concerts, house concerts, live streaming concerts online, Blab/Periscope. Anything which cannot be commoditized because it is ephemeral (not replayable), has VIP “exclusivity” or limited audience and/or IRL (In Real Life) qualities is scarce, and therefore more valuable.

- Allow Remixes: Musicians in the rap, EDM, and country genres know that remixes and collaborations are the key to elevating viability. Encourage other artists to remix and propagate your music. Partner with musicians in other genres and collaborate often on writing. Just make sure you receive proper attribution. Don’t worry as much about the money until you get the name recognition.

- Crowdfund: Understand your fans, invest in some nice design and create some unusual or quirky premium merchandise. Offer unique experience-based premiums that don’t cost a lot to create, so the margins are big. With the right offerings, platforms like Kickstarter, PledgeMusic, IndieGogo, RocketHub and Patreon can be successful revenue generators for smaller artists, but study others before jumping in.

So, what do you think? Have you had a particularly successful crowdfunding experience? Do you have band merchandise that has flown off the shelves? What “experiences in the context of the music” have you used to generate revenue? Please share in the comments section below.

8 comments

In the 70s and 80s I made money teaching guitar and playing in top 40 cover bands. In the 90’s I wrote and marketed CDs and toured. In the 2000s I started synch licensing, streaming, and downloads. I get paid from ASCAP, CDBaby, SoundExchange, and Getty Images. I no longer pursue gigs, as the pay is less than 30 years ago. I no longer sell physical merch, because the margin was not worth my time.

https://open.spotify.com/artist/11m1eWZOcuGHyNnE2m32SB

Chuck – Thank for leaving a comment. I think your experience is similar to several artists I have spoken to on this subject. It IS a lot of work – and a cash outlay – to have mercy consistently for sale. I think it comes down to whether the margins make it worth the effort to sell something, and that’s a calculation many forget to make. Popcorn is, well, popcorn. It’s such a money-maker because it’s so cheap to produce on site for a theater, and the audience is captive (and often hungry). I’m not sure bands have found a good array of items that are cheap to make but appealing to fans to buy, and that’s the conundrum.

Hi Solveig,

Great analysis and extra examples of Mulligan’s point.

I really like that graphic of three types of fans.

I have long been espousing that idea of a standard marketing funnel for musicians that feeds those superfans to the higher priced experiences.

BUT, I have, at best been a little misguided – at worst, totally wrong.

The revelation for me is that music fans aren’t like buyers of a tiered product line. And pushing them down a funnel with aggressive marketing and increased price offers doesn’t work like it does with standard upsells in many markets.

Rather we have to remember that a funnel of fans should look a bit more like a fluffy cloud of candy floss with a hard core sweet at the centre.

We don’t want to scare off the main fanbase and passive fanbase by over marketing. Rather we have to find a way that lets each fan at each level get what they want from the artist at the time and cost that they feel their relationship deserves.

So, make the offers to buy higher priced items nice and soft so as not to turn those fans off.

It’s definitely a challenge to get it right but in some recent work on Pledge Music campaigns it can be very effective.

Is that all waffle or did I make some sense?

Ian

“We don’t want to scare off the main fanbase and passive fanbase by over marketing.”

I totally agree, Ian. Although I think in general that this is the direction most consumer marketing is going. It’s the core of the content marketing/inbound marketing theory – offer, don’t oversell. I think the best consumer marketing employs all the amazing new targeted marketing techniques while still walking the line of being “promotional.” Music marketing and promotion (or really, selling the “experience of music”, which, to Milligan’s point, is about so much MORE than the music itself) is exactly like all other consumer product marketing, in my opinion. Feed consumers information at the top of the funnel, and guide them through the “fluffy cloud of candy floss” (love your description!) in such as way as to not alienate them, and then make it super easy, one-click, to purchase when they decide it’s time to purchase. I totally agree that aggressive marketing and increased price offers don’t work. I would just argue that they don’t work anymore in ANY consumer market because consumers have a lot of options, and they can so easily educate themselves about comparative pricing and product features. Crowdfunding is a perfect example of the “soft sell.” Customers are self-designating in the first place, so it’s not traditional “push” funnel marketing to start with. Perfect example – I am getting quite annoyed at all the promoted posts urging me to purchase tickets to Muse’s upcoming Seattle concert. I think they’ve served me about a dozen in the past week. Argh. All because I am on the Muse email list. They overdid that one for me. But, still, I am thinking of buying tickets…

Great article. One of my favorites. Thanks for sharing. Always super useful.

Related to this article, I’m also exploring the idea of “windowing” my next and 5th album and not having it on streaming services immediately… Was curious what your thoughts were on that ? (I just saw Adele did it recently… of course my career is nothing like Adele’s 😉 … )

Merci! You rock as always.

EJK

No, YOU rock, Eric! I think windowing in other ways is more productive for those of us who are not Adele. For example, providing your 5th album to your fans via a Patreon or Kickstarter list first, offering it on your website for download or streaming first, making it available first at a CD release or other event, and perhaps promoting a music video of the song before releasing the digital version to CD Baby distribution might be a better way to maximize the impact of the actual release to distribution. I think windowing on streaming is only effective if you have built up demand ahead of time, and if you are then trying to maximize download revenue, but I think for most of us regular artists it doesn’t really make that much sense.